By Rachel Carley

March 13, 1988

IN China, a place where taxes were once paid in bolts of silk and decorative needlework ranked among the most highly esteemed art forms, the ancient crafts of sericulture and embroidery are as firmly entrenched in national tradition as the daily bowl of rice.

By the middle of the Zhou dynasty (about 1066 B.C. to 256 B.C.) silk was already being exported to the Middle East, and its production had become a highly organized industry as early as the Han dynasty (202 B.C. to A.D. 220).

A contemporary outgrowth of silk production, the inseparable art of embroidery became so advanced that it eclipsed even painting in artistic importance. Professional embroiderers were among the country's most honored citizens, and their richly worked silks remained a mark of immense social and financial prestige throughout the country's dynastic history.

For visitors to Suzhou - one of China's primary embroidery centers - the Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute offers a first-hand encounter with this heritage. The institute was established in 1957 to do research in traditional Chinese embroideryand tapestry techniques, to develop new stitches and to train new generations of needle workers.

The center is known for double-sided embroidery, a Suzhou specialty, and for handwoven silk tapestries called ke-si, for detailed pictures worked in cross-stitch. Its location in Suzhou is particularly apt, as the city, founded about 600 B.C., was the site of the emperor's weaving workshop and has long been renowned for its embroidery, distinguished by smooth edges, flat surfaces and delicacy.

''We are proud to be continuing a tradition that goes back here for over two thousand years, with mothers teaching daughters and elder sisters teaching younger sisters,'' said Chao Ming Chu, an institute embroiderer who often sets down needle and thread to escort visitors through the center.

The center is equally proud of its modernization efforts. Only 18 embroidery stitches were in use in the country before the Communist China was founded in 1949. Most, including the chain, stem, satin and buttonhole stitches, date to the Han dynasty or before. ''Now we do more than 50,'' said Miss Chao, citing new inventions such as the elaborate ''tangled'' stitch, designed for extra texture and depth.

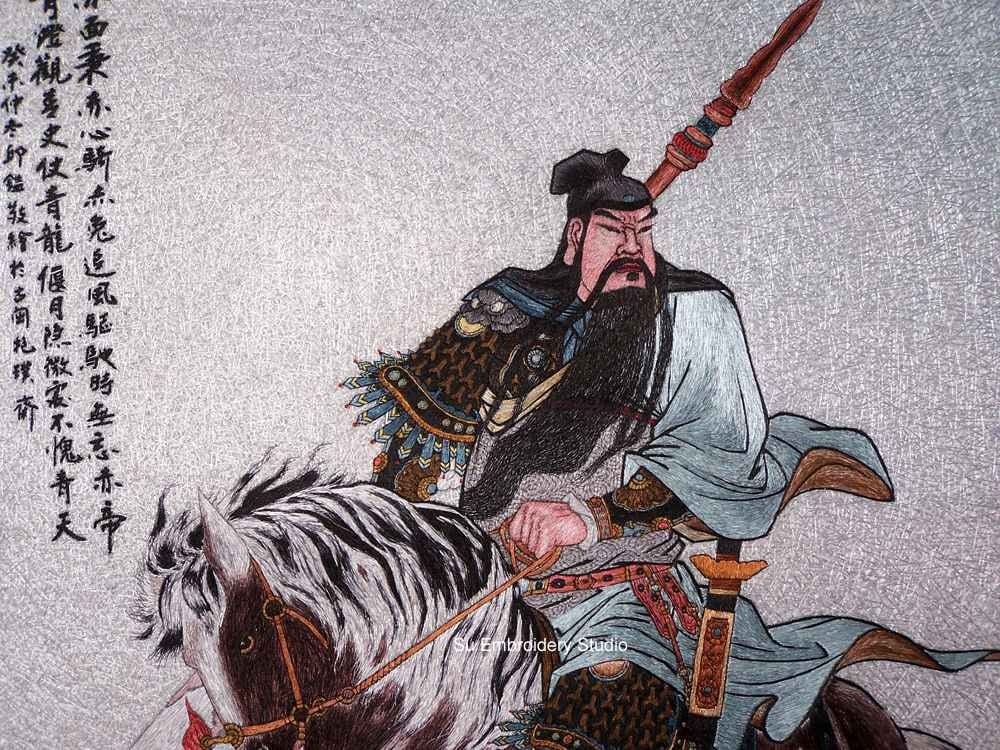

Subject matter, too, has branched out from the traditional animals, birds and flowers to include well-known Chinese landmarks, scenes from the daily life of workers and an occasional, if startling, copy of a European masterpiece such as the Mona Lisa - all designed to accommodate contemporary tastes.

In another nod to changing times, the institute has also challenged the sex barrier that once put Chinese needlework in the exclusive domain of women: of the center's 315 artisans, about one third are men. To gain admission to the rigorous three-year training program, all students must pass exams in both embroidery and painting. Good eyesight, too, is a prerequisite. To conserve it, the artisans break for a 15-minute rest every two hours and perform eye exercises twice a day.

Trainees begin after high school, at age 18 or 19, and commit their entire working life to the institute. Miss Chao, who is 32, joined the center 14 years ago, and expects to stay until she is 55, the customary retirement age for Chinese women.

A tour through the institute, which occupies the restored grounds and tile-roofed buildings of one of Suzhou's many former private garden estates - converted to public use after 1949 - offers a chance to observe the artisans at close hand.

Each studio, situated in the spacious rooms of the former residence and fitted with large casement windows for maximum natural light, is devoted to a different task. In one, artists hunch over individual tables making prototypes for the traditional flower and landscape designs, carefully painted on paper with water color and ink. For the more contemporary subjects, the embroiderers often work directly from greeting cards and magazine photographs.

An adjacent room sounds with the steady clack-clack of shuttle and loom, as weavers make the ke-si panels, a type of double-faced silk tapestry originated in the Song dynasty (960-1279) and traditionally used for scrolls, wall hangings and as ornamental appliques for imperial ceremonial dragon robes.

Tightly packed warp, or lengthwise, threads in varied colors - pale roses and deep reds, violets, dark teals and inky blues - infuse the ke-si with a special richness and dimension that is enhanced by the pinpricks of light that shine through tiny gaps left among the crosswise weft threads.

The shimmering compositions of enormous peonies and lotus blossoms, delicate butterflies and mist-shrouded mountains recall the moody, lyrical style of Song and Ming landscapes and traditional bird-and-flower paintings. The handwork is done on the same type of wooden loom used for the original ke-si, with dozens of shuttles used to carry the silk weft threads. A 2-by-3-foot panel takes about a year to complete.

In another studio, artisans bend quietly over wooden roller frames. Their task is the fragile double-sided embroidery, worked in a variety of satin, long-and-short and knotted stitches. Working on sheets of transparent gauze with silk strands so fine they are barely visible - a single thread is split into 48 filaments before use - the embroiderers wield two needles and two colors at the same time, continuously concealing the thread ends so that the piece is perfectly finished on both sides.

Minute detail and a careful blending achieve an effect of remarkable realism for these paintings in thread, which include delicate butterflies and blossoms, fluffy Shandong kittens and shimmering goldfish that appear suspended in water.

While many works are commissioned for international exhibition and government gifts, a wide selection is for sale in the institute's shop, tucked away off an enclosed courtyard amid the tile-roofed loggias, moon gates and rockeries of the restored gardens.

The shop itself has a brightly lighted modern interior lined with mirror-backed display cases designed to show off the stitchery from both sides. Except for some small embroideries made into flat fans ($30 to $100), all pieces are mounted on redwood frames with elaborately carved feet to make two-sided table and floor screens.

The smallest, 10-inch circular screens, display double-sided embroideries in natural vignettes: goldfish floating through a wisp of seaweed ($165), a pair of fragile butterflies ($138) or a long-haired kitten ($145).

As the pieces increase in size, the designs become more complicated. One 2-by-4-foot table screen ($1,436) depicts an exquisitely fragile butterfly worked in double embroidery on pale green gauze amid a burst of blossoming tulips. A more densely patterned ke-si panel incorporates a mass of blue iris with curling petals ($1,313). One of the most elaborate pieces encountered on a visit was a 4-by-5-foot screen of double embroidery alive with a family of squirrels caught in a tangle of grape vines ($8,273).

by Su Embroidery Studio (SES), Suzhou China

SES is dedicated to Chinese Silk Embroidery Art and High-End Custom Embroidery

Find SES's embroidery work at Chinese Silk Embroidery for Sale.